what a twist!

I recently revisited M. Night Shyamalan’s body of work. Shyamalan’s known for his use of plot twists, especially those revealed deep in the third act. But not all of his twists have been received equally well. The Sixth Sense is highly regarded, while his later films (such as The Village) were panned.

As a writer of suspenseful fiction, I’m always interested in the craft of heightening an audience’s reaction. But I don’t go in for very many plot twists in my work. There’s a great premium put on plot twists in narratives of all sorts, especially in our era of spoiler sensitivity. But in a good work of art, the plot twist should be one of the least important facets.

Let’s take The Sixth Sense as an example. (This should go without saying, but I will be SPOILING the big twist at the end of any works I discuss)

The only reason the big twist at the end works is because the whole story leading up to the twist works. We follow this adorable kid who can see dead people and the therapist who’s trying valiantly to reach him. After a series of highs and lows, the therapist and the kid realize that the “cure” isn’t to stop the kid from seeing ghosts – it’s to acclimate him to the trauma of these visions so that he can help the ghosts move on. The kid grows as a person because of this newfound strength and purpose.

It’s because of this new purpose that the twist at the end – that his therapist was actually dead all along – works. The therapist helps the kid master his gift; the kid helps the therapist move on from the mortal coil.

Without that thematic unity, and without the solid performances of Haley Joel Osment and Bruce Willis, the twist at the end is just a meaningless narrative flourish. The story could have worked without the twist – it would have been a B-minus thriller elevated by good performances – but the twist wouldn’t work without as good of a story.

There’s an episode of The Twilight Zone (the 1985 revival) called “Button, Button” in which a lower-working class married couple receives a visit from a mysterious stranger. He gives them a small box and makes them an offer: if they press the button on the box, someone they don’t know will die and they’ll receive a vast sum of money.

The couple debates the ethical implications of killing a random stranger for money. Maybe it’ll be someone with cancer! Maybe it’ll be a child! What if they do something really good with the money? And so on and so forth. (They investigate the box and find that there’s no mechanism inside that the button triggers)

The husband throws the box away to end the debate, but the wife can’t stop thinking about it and eventually pushes the button. The stranger shows up and pays them their money. He’s about to leave when the wife pleads to know who they killed. The stranger’s answer implies that the button always kills the previous person who pushed it.

Now:

This episode was based on a Richard Matheson short story of the same name. The story is identical in every respect except the ending. In the Matheson short story, the woman’s husband dies. When the stranger shows up with the payday, he makes some arch comment along the lines of “never really knowing” the person you marry.

Matheson hated the Twilight Zone version and I’ve never understood why. It’s a substantially better ending!

Matheson’s version hinges on a coy little semantic twist of what it means to “know” someone. But the TV version makes the twist matter! The entire episode revolves around an ordinary couple talking themselves into something monstrous through a mix of rationalization and curiosity. But whether the wife survives long enough to enjoy the payoff depends on whether the next person to get the box – a total stranger – is more ethical than she was.

(Note: the ferry scene in the climax of THE DARK KNIGHT works for a similar reason)

A plot twist can be a tool to heighten emotion, but only if there’s already emotional investment present. “The sidekick was working for the bad guys all along!” only works if you like the sidekick. Without that, a plot twist is just a trick.

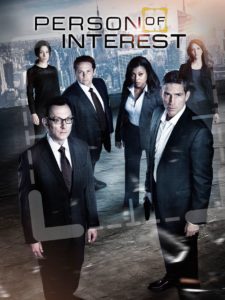

Two of my favorite TV series of the past 10 years – shows that I keep coming back to – are Burn Notice and Person of Interest. As formula shows, they work: a retired spy with exceptional skills helps innocent people solve problems that the cops can’t help with. They have a variety of contacts and allies – some intimate, some reluctant – who help them on their way. They’ve done bad things in their past, but their freelance vigilantism gives them a chance at redemption.

Two of my favorite TV series of the past 10 years – shows that I keep coming back to – are Burn Notice and Person of Interest. As formula shows, they work: a retired spy with exceptional skills helps innocent people solve problems that the cops can’t help with. They have a variety of contacts and allies – some intimate, some reluctant – who help them on their way. They’ve done bad things in their past, but their freelance vigilantism gives them a chance at redemption.